Oral Hormonal Contraceptives

Contraception

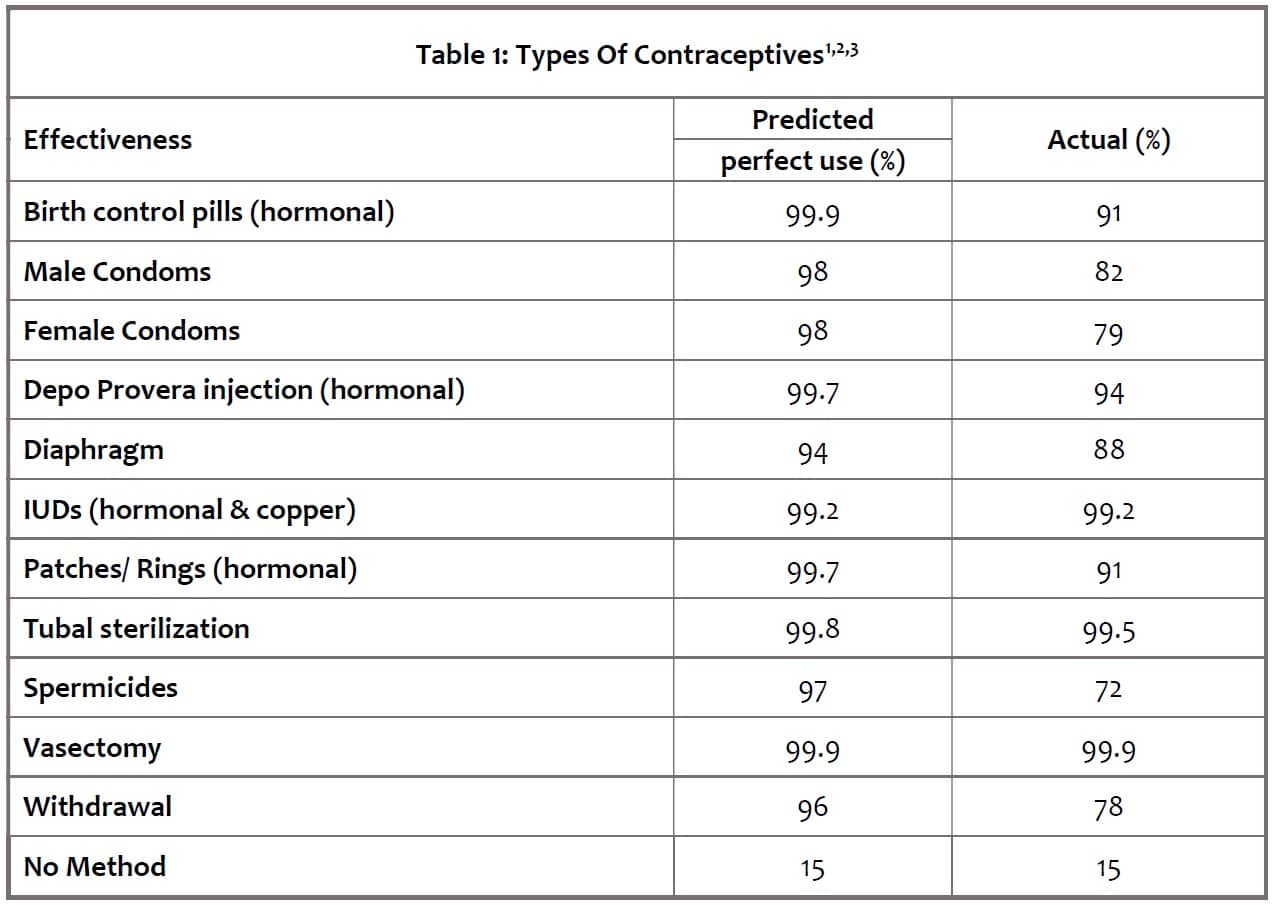

Contraception is defined as actions or a technique that prevent pregnancy by disrupting the normal process of ovulation, fertilization and implantation1. Contraceptives are physical or medical products that assist with contraception. There are a wide variety of contraceptives in the broad method categories of barrier, hormonal, spermicidal, intrauterine and surgical.

Tubal ligation, hysterectomy and male vasectomy are irreversible surgical contraceptive measures whereas other methods are reversible or temporary.

Tubal ligation, hysterectomy and male vasectomy are irreversible surgical contraceptive measures whereas other methods are reversible or temporary.

Each of the reversible method’s effectiveness is dependent on consistent and proper use; thus, the real-world effectiveness is lower than predicted by the ideal use. Contraceptives that require daily administration like daily oral contraceptives or application prior to each intercourse like spermicides tend to be less effective as the chances for human error is increased. Convenience and the likelihood of consistent adherence to a particular method is an important consideration when choosing a contraceptive. This presentation will focus on oral hormonal contraceptives.

It is important to note that other than condoms, no other contraceptive methods reduce the risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STIs). The use of a condom should be used in conjunction with other contraceptive methods to prevent STIs.

Hormonal Contraceptives

There are 2 general types of hormonal contraceptives: 1) combined – which contains both a synthetic estrogen and progestin, and 2) progestin only

Combined hormone contraceptives are available in Canada as daily oral pill, transdermal patch, vaginal ring forms. Progestin-only contraceptives are available as a daily oral pill and as an intramuscular injection. Intrauterine devices (IUDs) can be either progesterone-medicated or non-medicated copper.

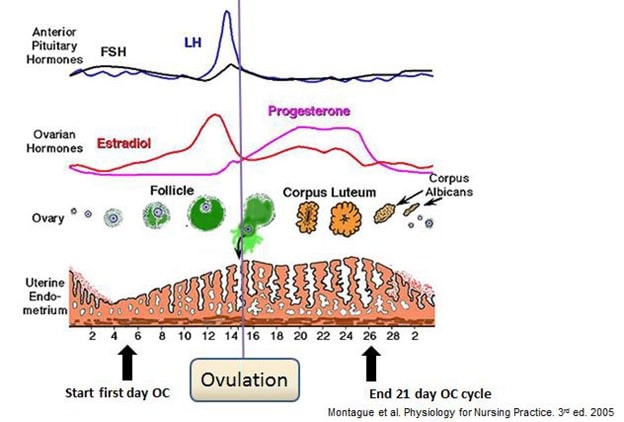

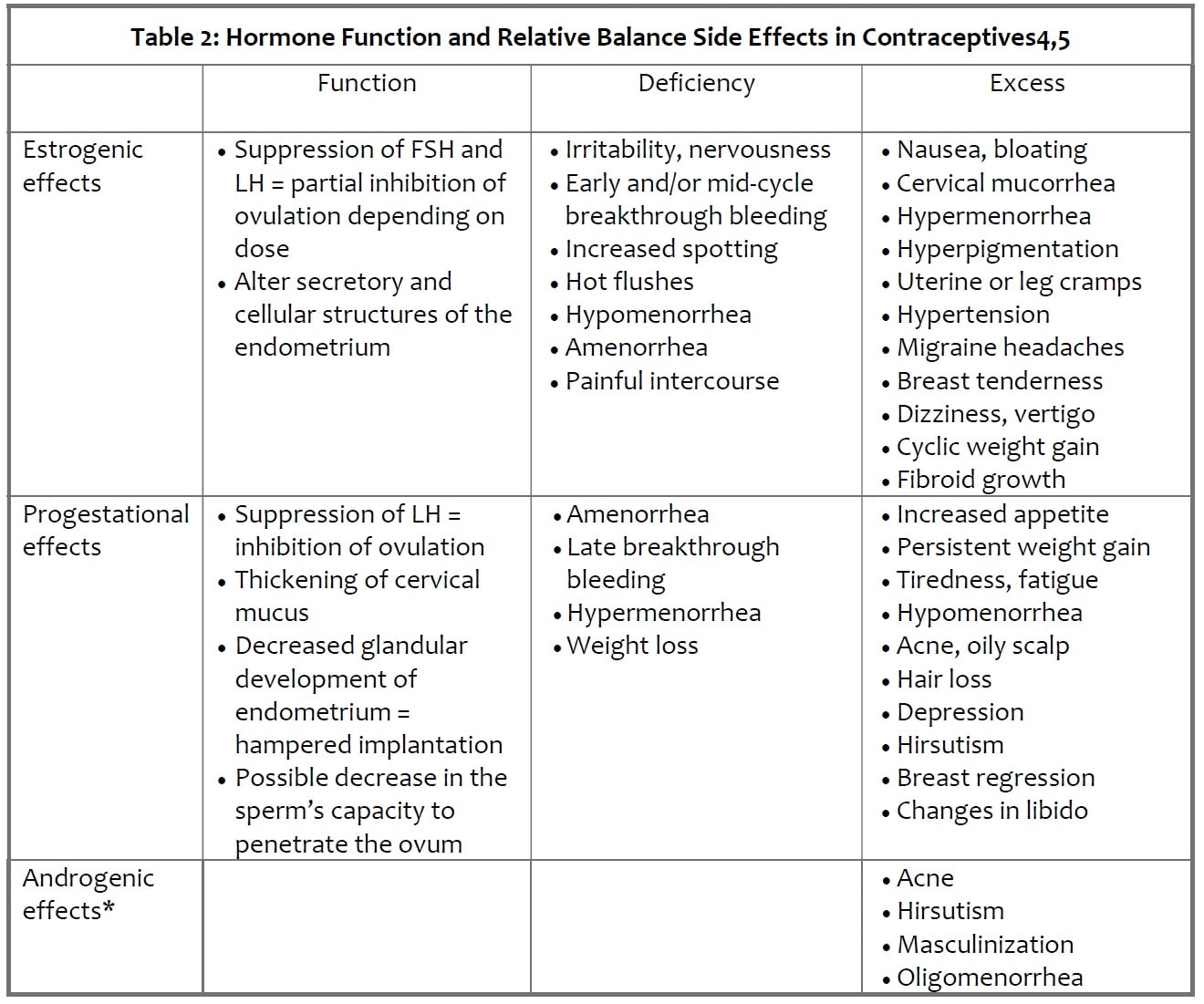

Hormonal contraceptives function by stabilizing hormone levels which suppress the spike release of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). The sharp increases in LH and FSH are necessary for ovulation and thus hormonal contraceptives prevent ovulation. Figure 1 illustrates the hormone levels in the average menstrual cycle. Hormonal contraceptives also cause changes at the cervix and endometrial lining to make sperm entry and implantation of a fertilized egg less favourable as outlined in Table 2 below 4. IUDs function mainly by decreasing sperm motility and altering the uterine lining to discourage implantation.

* Oral contraceptives do not contain androgens (ie: testosterone) as an ingredient. However, progesterins can be metabolised in the body to testosterone and mediate androgenic effects. Different progestins have differing rates of metabolism to testosterone, so various oral hormonal contraceptives will have varying androgenic activity depending on the amount and type of progestin.

Daily Oral Contraceptives

Oral contraceptives, especially the combined oral contraceptives (COCs), are the most common hormonal contraceptives used by women in North America. They are commonly referred to as birth control.

Before starting a COC, each woman must be assessed for contraindication and additional risk factors as well as advantages and disadvantages of using COC.

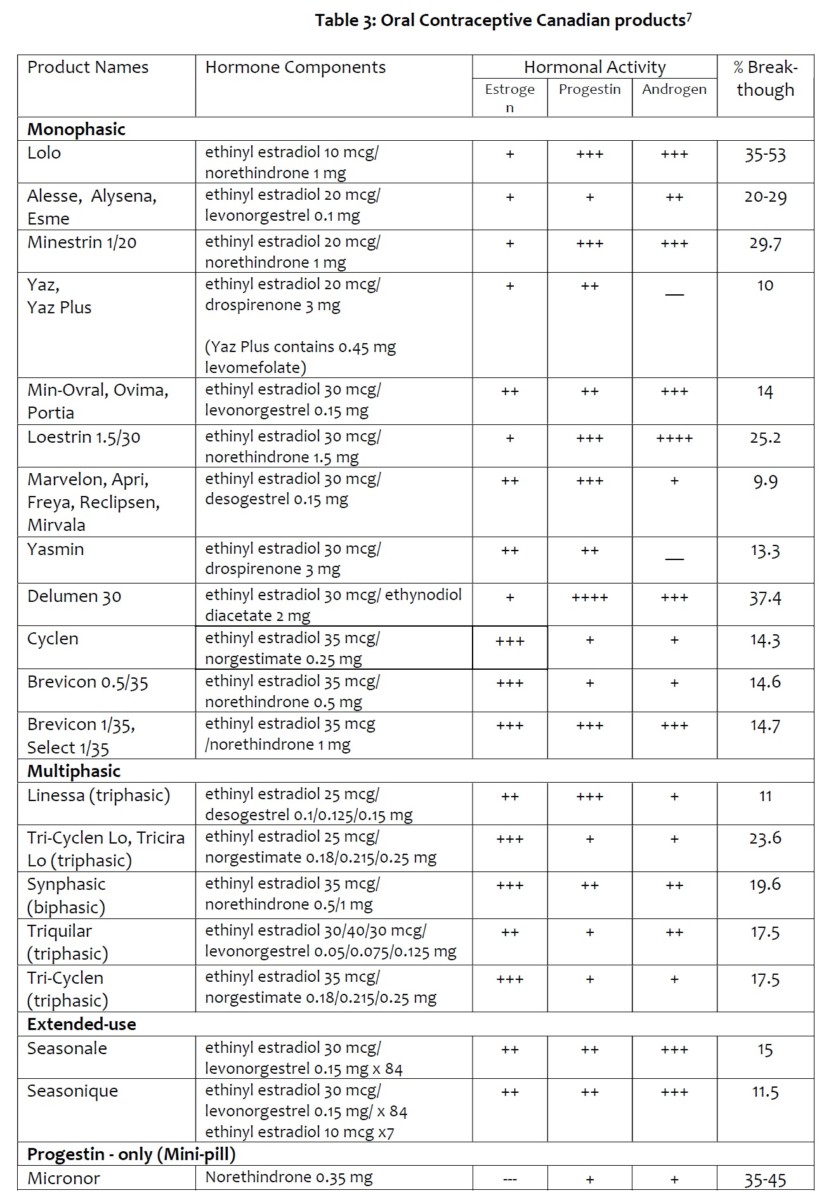

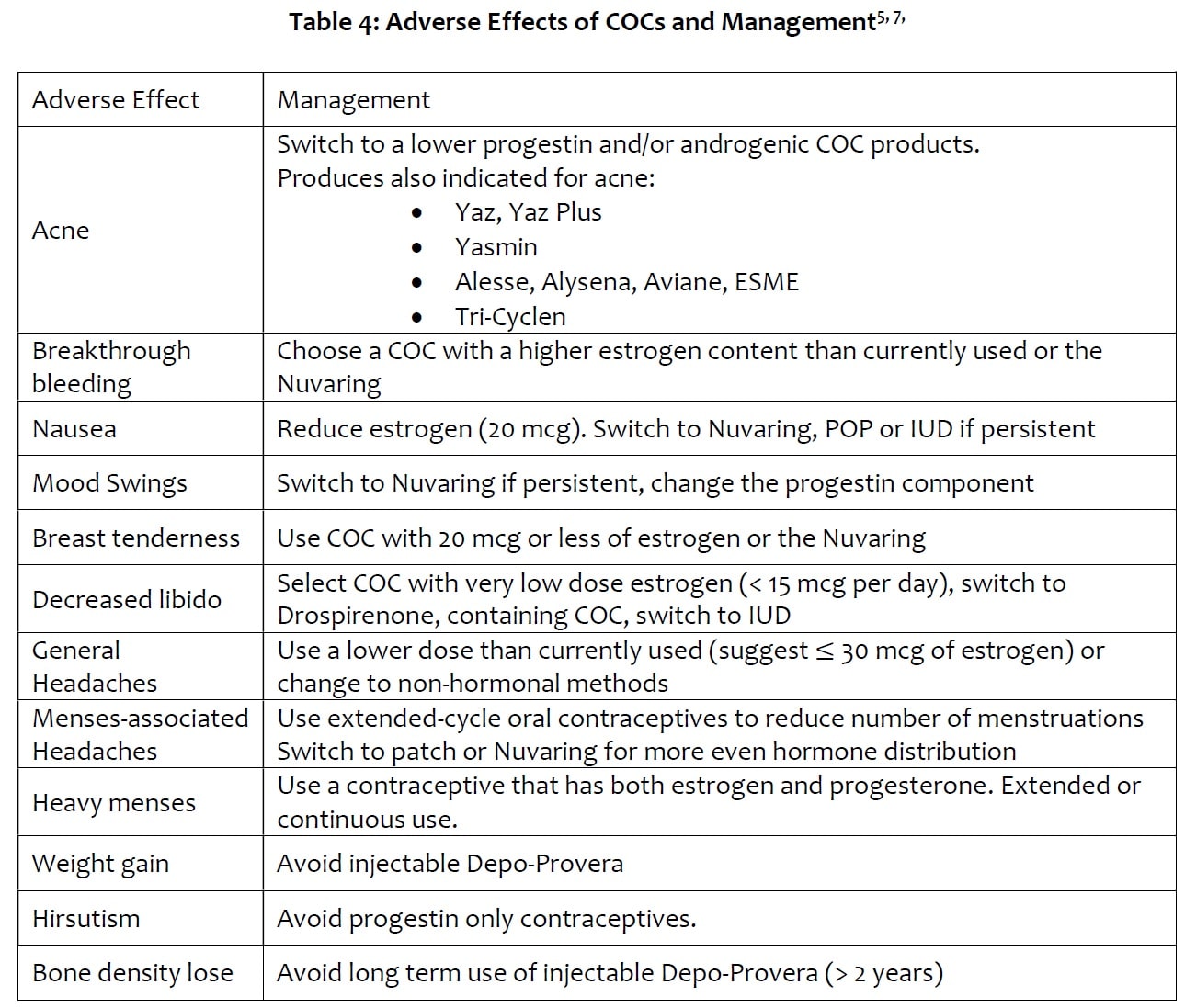

Advantages: non-invasive, simple to initiate and discontinue; many strengths and product varieties available (Table 3); other potential health benefits6: cycle regulation; decrease menstrual flow, iron deficiency anemia; decrease dysmenorrhea, premenstrual or perimenopausal symptoms; decrease acne, hirsutism (but may aggravate as well depending on the hormonal composition and individual compatibility); decrease pelvic inflammatory disease; decrease endometrial and ovarian cancer; decrease fibroids (but may aggravate as well depending on hormonal composition and individual compatibility); increase bone mineral density – effect of estrogen.

Disadvantages4: very reliant on daily use at the same time of daily for effect – vulnerable to human administration errors (Progestin-only pills must be taken no more than 3 hours after the scheduled time daily); does not protect against STIs; must consider interactions with other medications, contraindications and side effects.

Risk factors4,7: breast cancer or hormone-dependent cancer -> use non-hormonal methods; cerebrovascular disease, history of cerebrovascular accident; complicated valvular heart disease; current or past history of venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism, known thrombogenic or prothrombin mutations and antithrombin deficiencies; diabetes with microvascular complications; history of or current MI or ischemic heart disease, vascular disease; <6 weeks postpartum if breastfeeding -> use progestin-only or barrier methods; migraines with aura at any age; hypertension (SBP ≥160 mm Hg or DBP ≥100 mm Hg); severe cirrhosis or liver tumor; smoker >35 years of age (≥15 cigarettes/day) -> use progesterone-only or non-hormonal; current pregnancy; unusual vaginal bleeding – may be a sign of an STI or cancer; certain medications [Antiseizure – phenytoin, carbamazepine, primidone, phenylbutazone, felbamate, ozcarbazine and lamotrigine (lamotrigine levels decreased by progestins); Antibiotics – rifampin/rifampicin; Antivirals – ritonavir]

The World Health Organization also recommends that for women < 35 years and who smoke to use an oral contraceptive that contains 35 mcg or less of estrogen8. Post-partum and breastfeeding women should use progesterone-only or non-hormonal methods7.

Antibiotics and Oral Contraceptives

The only antibiotic that has been proven consistently to decrease the effectiveness of oral hormonal contraceptives so far is rifampin, also known as rifampicin7. When using this medication with birth control, a back-up method must also be used. Other antibiotics are generally considered safe to use with oral hormonal contraceptives without a back-up7. The theory behind the potential interference of antibiotics with COCs is due to how estrogen is metabolized. Estrogen is metabolized by the liver and excreted into the bile. The bile is then used to help digest food in the intestines. The bacteria in the normal intestinal flora can digest the modified estrogen back to a form that can be re-absorbed by the body and thus contribute to the blood levels of estrogen. Antibiotics kill a portion of the normal flora while in use and there was a concern that this may decrease estrogen levels in the body. For antibiotics other than rifampicin, this has not been shown to significantly decrease the efficacy of COCs, however pharmacist and doctors may still advise the use of a back-up method out of caution9.

If antibiotics cause vomiting within 2 hours of taking an oral contraceptive or severe diarrhea, this may decrease the absorption of the tablet and decrease its effectiveness. If this happens, a back-up contraceptive is recommended9.

Mono vs Multiphasic

Monophasic COCs are products that contain the same level of hormones in each of the active pills. Multiphasic COCs have active pills that contain different amounts of hormones on different days of the cycle. For example, Tri-Cyclen has the same amount of estrogen in each of the 21 tablet, but the amount of the progestin changes (7 days of 0.18mg, then 7 days of 0.215mg, then 7 days of 0.25mg). Multiphasic COCs were designed to more closely mimic the natural rising and falling hormone levels while still suppressing ovulation10. The total monthly dose of hormones can be lower with multiphasic COCs compared to some monophasic ones They can be helpful for women who have persistent side effects (Table 2) from monophasic COCs.

Most COCs can come in the 21-pill or 28-pill versions. In the 21-pill version, there are 21 tablets that all contain hormones that lasts for 3 weeks. For the last 7 days of the cycle, there are no pills and a menstrual period takes place. In the 28-pill version, there are 21 tablets with hormones and 7 tablets of placebo, which allows for a menstrual period. The benefit of the 28-pill version is that it helps to maintain the habit of taking a tablet everyday while allowing for a monthly menstrual period. There are a few multiphasic and extended use products that have a different pill pattern.

Reducing the Number of Periods – Continual and Extended-use

Oral contraceptives can be used by women who are seeking to reduce the number of menstrual period for either medical or convenience purposes. There is no scientific evidence so far that monthly menstrual periods are necessary for optimal health11. Therapeutic amenorrhea (suppression of menstrual periods with medical interventions) can have the benefits of reducing several conditions including premenopausal syndrome (PMS), iron deficiency anemia, menstrual associated headaches and chronic pelvic pain, etc.

Seasonale and Seasonique are products designed for extended use, 12 weeks of hormone containing tablets per pack. Seasonique is formulated with 3 placebo tablets that allows for a menstrual period every 12 weeks. Regular COCs can be used in a continuous fashion to achieve the same results. Women would use the 21 hormonal tablets of each pack then immediately start a new pack afterwards without the 7-day break or placebo pills.

Often at the early stages of therapy breakthrough bleeding can often occur at unpredictable times. For example, bleeding may take place after no menstrual periods in 8-16 weeks with extended or continuous use. When heavier breakthrough bleeding or spotting for several days take place after at least 3 months of treatment, practitioners advise to stop COC for maximum 3 days to allow a menstrual period. Do not take a break before 3 months. In research, in general women achieve amenorrhea after 1 year of treatment12,13. Extended and continuous use COC reduce the number of menstrual periods per year, however when breakthrough bleeding occurs it is at unpredictable times.

Oral Contraceptives and Mood

Hormone levels influence mood. Women can experience changes to their mood when starting, changing and stopping oral contraceptives7. Changes are very individual and can be either an improvement or worsening of mood. Reduction in PMS related mood issues and mood swings are a potential benefit of hormonal contraceptives7. There has been conflicting research on the associate between hormonal contraceptives (especially the progestin component on adolescents) and depression with the latest research finding no associate14,15. More research is needed in this area. Women who have underlying mood disorders or have higher risk factors for mood disorders are more vulnerable to mood effects14. For women who do experience decreased mood that does not return to normal after 3 months of oral contraceptives should report this to their health practitioner.

Starting Oral Contraceptives

There are 3 general methods to starting oral contraceptives16,17: Quick start – start taking as soon contraceptives are obtained, irrespective of timeline to menstrual cycle. Use back-up method for the first 7 days; Sunday start – Take first tablet on a Sunday. Use back-up method of the first 7 days; First day of period start – take first tablet on first day of next menstrual period. No back-up method required.

When initiating oral COCs or when health status changes, women may experience adverse effects due to suboptimal hormone balance. The disruptions are more common in the first 1-3 months of initiating a COC and fade with continual use. When adverse effects, including but not limited to Table 4, persist for more than 3 months and/or intolerable, the regiment can be switched to another product with a more suitable hormone composition7.

Cardiovascular and Clotting Risk

Hormonal contraceptives which contain estrogen may slightly increase the risk for developing cardiovascular issues such as stroke and heart attacks. Research suggest 7 more cases of heart attack per every hundred thousand women years (number of women x years of use)18. In non-smoking, health women under 35 years of age with no other risk factors for cardiovascular disease the absolute risk increase is minimal19.

Estrogen containing systemic contraceptives is associated with an increase in venous thrombosis (inappropriate clotting in the veins) but to a lesser extent compared to the risk in pregnancy. Pregnancy increases clotting risk by 6-10 times from baseline. The incidence of VTE in women not on oral contraceptives is 0.19–0.37 per 1000 woman-years. The risk for VTE increases by 1.5 – 3 times for women on COCs to about 0.57 – 1.11 per 1000 women-years20.

Breast Cancer Risk

Overall, the risk of developing breast cancer is low. A 20-year-old has a 0.1% chance of developing breast cancer in the next 10 years21. Current users of oral contraceptives with estrogen have slightly increased risk for breast cancer but that risk decreases with time since last use and is no longer apparent after 10 years of past use22. A total lifetime duration of use for >15 years compared to never having used COCs is associated with a 50% increased risk of breast cancer in women23. Moderate- and high-dose estrogen preparations as well as some triphasic formulas have been found to increase the risk of breast cancer compared to other products19. Women with a known family history of breast cancer or have other risk factor may want to consider other contraceptive methods with lower estrogen content that are monophasic or methods without estrogen.

Missed Doses

The effectiveness of oral contraceptives is highly dependent on consistent daily use. Missing even a few days can result in the loss of contraceptive effect.

For progestin-only products, if a dose is miss past 3 hours late24, 25: take a missed pill as soon as remembered; then go back to taking progestin-only pills at the regular time; but be sure to use a backup method (such as a condom and/or a spermicide) at every sexual encounter for the next 48 hours. If more than one dose is miss or if not sure what to do about the pills missed, keep taking progestin-only pills and use a backup method (minimum 7 days) until a doctor can be consulted.

For most combination COC17, 25:

Missed one pill: Take it as soon as possible and take the next pill at the usual time. Might take two pills in one day.

Missed 2 pills in a row: In first 2 weeks – Take two pills the day remembered and two pills the next day; then on the 3rd day, take one pill a day until the pack is finished; use a non-hormonal back-up method of birth control for intercourse in the seven days after you miss the 2 pills; consider taking an emergency contraceptive if unprotected intercourse took place within the last 5 days. Third week – Safely dispose of the rest of the pill pack and start a new pack that same day. Or continue taking the remainder of the active hormone pills of the current pack, but do not take a hormone-free week – discard the placebo pills and start a new pack; use a non-hormonal back-up method of birth control for 7 days after missed pills. Consider taking an emergency contraceptive if unprotected intercourse took place within the last 5 days; may not have a period this month; consider taking an emergency contraceptive if unprotected intercourse took place within the last 5 days.

Missed 3 or more in a row: Anytime in the cycle – Safely dispose of the rest of the pill pack and start a new pack that same day. Or continue taking the remainder of the active hormone pills of the current pack, but do not take a hormone-free week – discard the placebo pills and start a new pack; use a non-hormonal back-up method of birth control for intercourse in the seven days after missed the pills; may not have a period this month; consider taking an emergency contraceptive if unprotected intercourse took place within the last 5 days

If more than one period is skipped after an episode of missed oral contraceptives, it is advisable to conduct a pregnancy test.

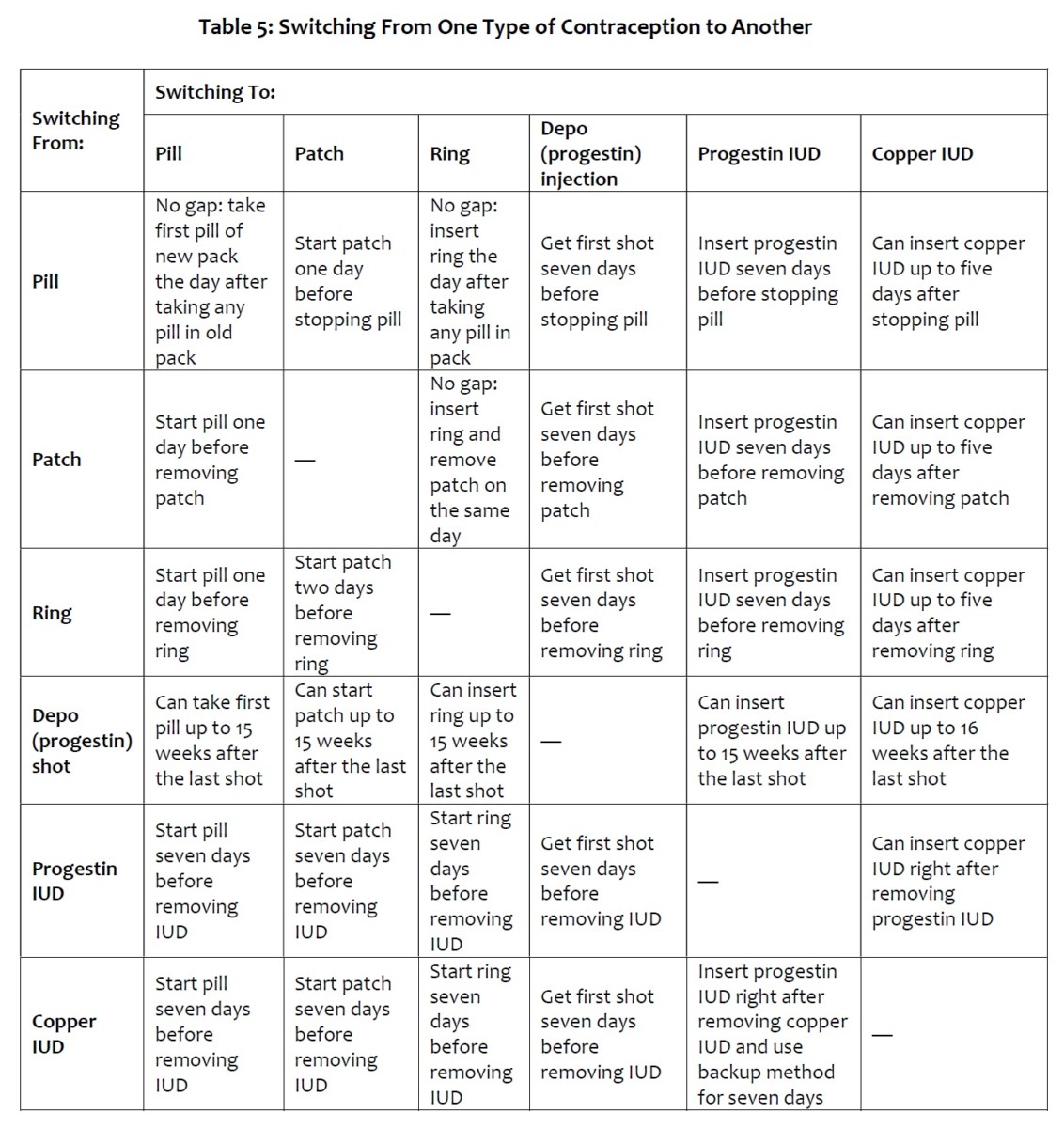

How to Switch From Type of Contraceptive Method to Another26

The following are recommendations when switching contraceptive methods in order to minimize loss of contraception and symptoms associate with fluctuating hormone levels

Oral Contraceptives on Fertility and Menopause

The use of hormonal contraceptives has not been found to decrease fertility after its discontinuation. Women can become pregnant within days of discontinuation of oral contraceptives depending on the time of the cycle. Generally, after one menstrual cycle post-discontinuing oral hormonal contraceptives, fertility returns to the baseline rate for a woman according to her age, genetics and health status27.

Hormonal contraceptives may decrease pre-menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes or vaginal dryness, but they have not been shown to affect the age of onset for menopause28, 29.

Discontinuing Oral Contraceptives

Oral contraceptives can be discontinued at any time. The most common reason for discontinuing hormonal contraceptives is for planning pregnancy. As discussed above, fertility returns very quickly after discontinuation of oral contraceptives. When oral contraceptives are stopped, withdrawal bleeding will take place like a menstrual period.

Women who have entered menopause (one year post last menstrual period when not on continuous use oral contraceptives), should discontinue oral contraceptives28, 29. Women on continuous use oral contraceptives who have achieved amenorrhea should discuss with their healthcare provider as to how to assess for the onset of menopause.

Other reasons to discontinue oral contraceptives include personal preference, intolerable side effects, discovery of an unintended pregnancy, change in medical status, addition of incompatible medications or inaccessibility.

When discontinuing hormonal contraceptives, women are likely to experience changes to their menstrual patterns as the body re-adjusts to the withdrawal of hormones within the first 3 months, even though normal fertility can be restored sooner. It should be discussed with a doctor if the menstrual cycle is still erratic after a year post hormone contraceptive. Withdrawal of hormonal contraceptives can also bring about the return of symptoms such as acne, PMS, heavier bleeding, etc. that it was controlling previously30.

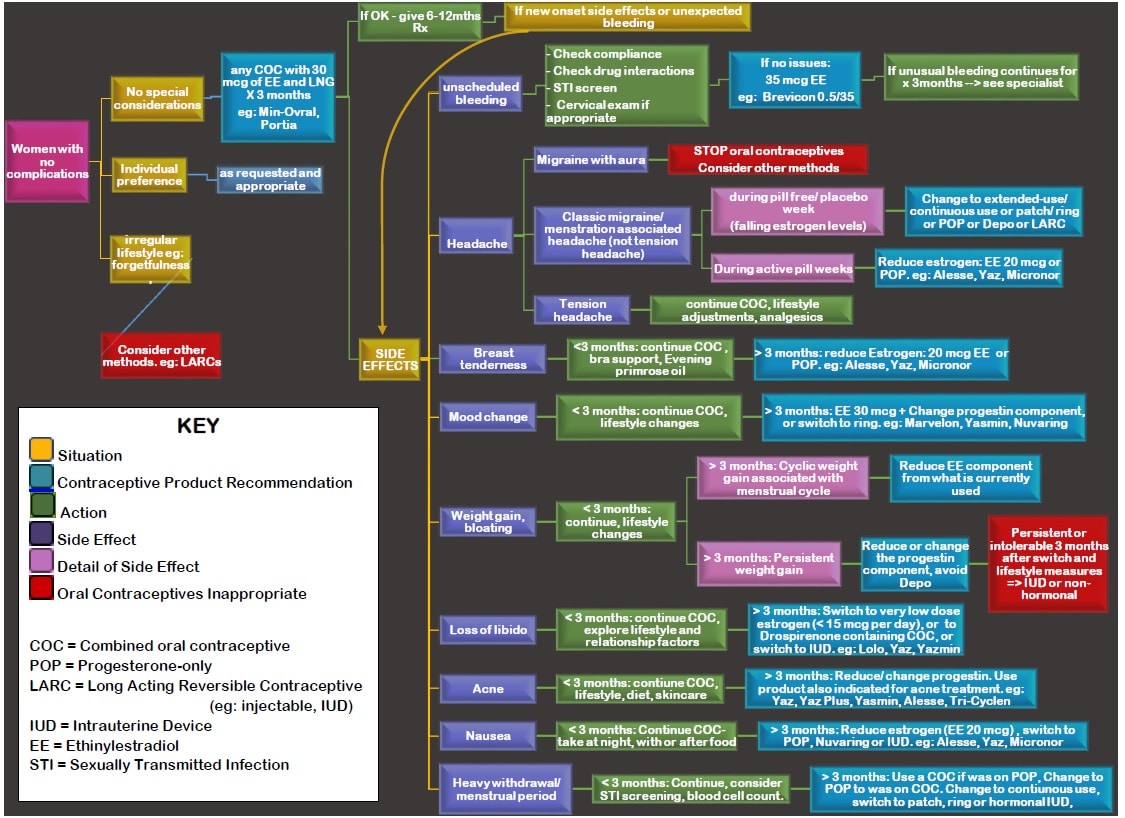

Suggested COC Initiation Pathway for Women with No Restriction to using COCs31, 32, 33, 34

Every women’s body is different and while one contraceptive method may work for one person, it may not be the best option for another. Below, we have put together a recommendation for initiation/continuation pathway for contraceptive options based on the patient’s situation, and side affects.

References

- Contraception [Internet]. TheFreeDictionary.com. 2018 [cited 29 May 2018]. Available from: https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/contraception

- Family planning: A global handbook for providers. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Center for Communication Programs, INFO Project, WHO; 2018.

- Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception [Internet]. 2011 [cited 29 May 2018];83(5):397-404. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3638209/

- De Groot L, Chrousos G, Dungan K. Endotex [Internet]. South Darthmouth MA: MDText.com Inc; 2010 [cited 2 June 2018]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279148/

- Grossman Barr N. Managing Adverse Effects of Hormonal Contraceptives. American Family Physician [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2 June 2018];82(12):1499-1506. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2010/1215/p1499.html

- Schindler A. Non-Contraceptive Benefits of Oral Hormonal Contraceptives. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2 June 2018];11(1):41-47. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3693657/

- Graves G. Contraception In: Jovaisas, Barbara, editor. Therapeutics [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Pharmacists Association; c2015 [updated March 2018; cited 2018 June 02]. Available from: http://www.e-therapeutics.ca. Also available in paper copy from the publisher.

- WHO Scientific Group on Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception: Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception: Report of the WHO Scientific Group. WHO Technical Report 877. Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- Orme M, Back D. Factors affecting the enterohepatic circulation of oral contraceptive steroids. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology [Internet]. 1990;163(6):2146-2152. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/000293789090555L

- Stacey D. Multiphasic vs. Monophasic Birth Control Pills [Internet]. Verywell Health. 2018 [cited 9 June 2018]. Available from: https://www.verywellhealth.com/types-of-combination-pills-906935

- Hillard P. Menstrual suppression: current perspectives. International Journal of Women’s Health [Internet]. 2014 [cited 13 June 2018];6:631-637. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4075955/

- Johnson J, Wright K. Evaluation of extended and continuous use oral contraceptives. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management [Internet]. 2008;4(5):905-911. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2621397/

- OMAHA OBgyn Associates, PC. Instructions for Taking Birth Control Pills Continuously [Internet]. p. 1. Available from: http://www.omahaobgyn.com/images/forms/ContinuousBCP.pdf

- Skovlund C, Mørch L, Kessing L, Lidegaard Ø. Association of Hormonal Contraception With Depression. JAMA Psychiatry [Internet]. 2016 [cited 10 June 2018];73(11):1154. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/2552796

- Worly B, Gur T, Schaffir J. The relationship between progestin hormonal contraception and depression: a systematic review. Contraception [Internet]. 2018 [cited 10 June 2018];97(6):478-489. Available from: https://www.contraceptionjournal.org/article/S0010-7824(18)30032-5/pdf

- How to Take Birth Control Pills [Internet]. HealthLink BC. 2018 [cited 6 June 2018]. Available from: https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/health-topics/tn10330

- CPS [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2017 [cited 2018 June 06]. Alesse [product monograph]. Available from: http://www.e-therapeutics.ca. Also available in paper copy from the publisher.

- Acute myocardial infarction and combined oral contraceptives: results of an international multicentre case-control study. The Lancet [Internet]. 1997;349(9060):1202-1209. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/pubmed/9130941?dopt=Abstract

- Weill A, Dalichampt M, Raguideau F, Ricordeau P, Blotière P, Rudant J et al. Low dose oestrogen combined oral contraception and risk of pulmonary embolism, stroke, and myocardial infarction in five million French women: cohort study. BMJ [Internet]. 2016 [cited 6 June 2018];:i2002. Available from: https://www-bmj-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/353/bmj.i2002.long

- Kujovich J. Hormones and pregnancy: thromboembolic risks for women. British Journal of Haematology [Internet]. 2004;126(4):443-454. Available from: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05041.x

- American Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts & figures 2015-2016. Atlanta (GA): American Cancer Society; 2015. Available from: www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2015-2016.pdf.

- Beaber E, Buist D, Barlow W, Malone K, Reed S, Li C. Recent Oral Contraceptive Use by Formulation and Breast Cancer Risk among Women 20 to 49 Years of Age. Cancer Research [Internet]. 2014 [cited 6 June 2018];74(15):4078-4089. Available from: http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/74/15/4078.long

- Bhupathiraju S, Grodstein F, Stampfer M, Willett W, Hu F, Manson J. Exogenous Hormone Use: Oral Contraceptives, Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy, and Health Outcomes in the Nurses’ Health Study. American Journal of Public Health [Internet]. 2016 [cited 6 June 2018];106(9):1631-1637. Available from: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303349?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3Dpubmed&

- CPS [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2017 [cited 2018 June 06]. Micronor [product monograph]. Available from: http://www.e-therapeutics.ca. Also available in paper copy from the publisher.

- SOS [Internet]. Sexandu.ca. 2018 [cited 8 June 2018]. Available from: https://www.sexandu.ca/sos/sos.php

- Lesnewski R, Prine L, Ginzburg R. Preventing Gaps When Switching Contraceptives. American Family Physician [Internet]. 2011 [cited 10 June 2018];83(5):567-570. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/0301/p567.html

- Cronin M, Schellschmidt I, Dinger J. Rate of Pregnancy After Using Drospirenone and Other Progestin-Containing Oral Contraceptives. Obstetrics & Gynecology [Internet]. 2009 [cited 10 June 2018];114(3):616-622. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2009/09000/Rate_of_Pregnancy_After_Using_Drospirenone_and.20.aspx

- Dvornyk V, Long J, Liu P, Zhao L, Shen H, Recker R et al. Predictive factors for age at menopause in Caucasian females. Maturitas [Internet]. 2006 [cited 10 June 2018];54(1):19-26. Available from: https://www.maturitas.org/article/S0378-5122(05)00220-3/fulltext

- de Vries E, den Tonkelaar I, van Noor P, van der Schouw Y, te Velde E, Peeters P. Oral contraceptive use in relation to age at menopause in the DOM cohort. Human Reproduction [Internet]. 2001 [cited 10 June 2018];16(8):1657-1662. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/humrep/article/16/8/1657/624673

- Mulpeter K. http://www.health.com [Internet]. Health. 2017 [cited 10 June 2018]. Available from: http://www.health.com/birth-control/stopping-birth-control

- Mansour D, Searle S, Smith D, Gray S, Hill C, Andrews G et al. Rational prescribing of oral contraceptives [Internet]. Surrey, UK: Consiuent Health; 2015 p. 9-11. Available from: http://www.knowyourcontraceptives.co.uk/downloads/…/Rational-Prescribing-Document.pdf.

- De Groot L, Chrousos G, Dungan K. Endotex [Internet]. South Darthmouth MA: MDText.com Inc; 2010 [cited 2 June 2018]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279148/

- Grossman Barr N. Managing Adverse Effects of Hormonal Contraceptives. American Family Physician [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2 June 2018];82(12):1499-1506. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2010/1215/p1499.html

- Graves G. Contraception In: Jovaisas, Barbara, editor. Therapeutics [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Pharmacists Association; c2015 [updated March 2018; cited 2018 June 02]. Available from: http://www.e-therapeutics.ca. Also available in paper copy from the publisher.